I worked on Dauntless. I was the tenth employee of Phoenix Labs and built an extraordinary amount of code and infrastructure for the game. I wasn’t the only one–everyone at Phoenix Labs contributed to something amazing.

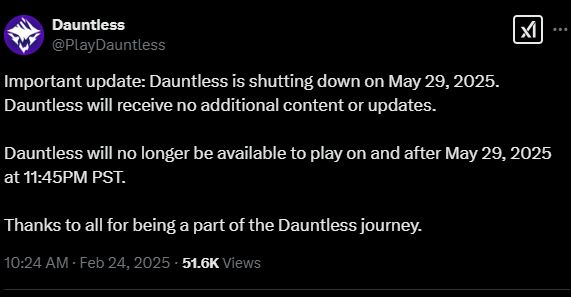

I was disappointed to hear the news:

What I find most distressing is the vast quantity of great tools and code that will disappear while making games become progressively more difficult.

I won’t discuss what led to these circumstances (partly due to NDA).

What I am interested in is the vast quantity of code.

In Canada, we have SR&ED: Scientific Research and Experimental Development tax incentives. These can be a substantial amount of employee wages. They represent an investment in Canadian technology and innovation. It is tragic to see this technology and innovation be lost to cancelled projects and closed companies.

How SR&ED operates needs to change to continue to foster technology and innovation. The degree of tax credit received depends on how long the company has exclusive access to the technology. The longer they have exclusive access, the less the tax credit. When that time expires, or other circumstances transpire (such as ending the relevant product or closure of the company), Canada acquires the rights to the technology to license, sell, or release publicly.

Instead of reinventing technology (and more SR&ED tax credits), technology can be reintroduced to the ecosystem when time limits (or other events) occur.